Solving the mystery of Marie Krivitzky

- Jessica Feinstein

- Dec 12, 2023

- 9 min read

One of the highlights of 2023 has been removing Marie Krivitzky from my list of unsolved mysteries.

I had always known that Marie was a second cousin of my mother’s mother, Judy, but I couldn’t work out how, when we didn’t have any ancestors called Krivitzky. My grandfather Harry mentioned Marie in a list of his possessions that I have:

The other clues I had were three undated photos and three letters. The first letter was written by Marie to my grandparents Judy and Harry, dated 14 May 1933, a few weeks after the birth of their first son, my uncle David:

The notepaper is headed Roman Krivitzky, with the address 6 Avenue Marceau, Paris. Marie mentions someone called Paul, who is taking exams, and her father, who is travelling. (I can’t work out the next sentence about ____ who will spend the summer holidays with ____ and us all in the South of France.)

The second letter was to my grandmother Judy in January 1936, written from Warsaw just a week after my mother Ruth was born.

Again, she mentions ____ and his wife, who send their love and greetings.

And the third letter was to my uncle David in 1958, from Cannes:

I had done a lot of Googling to try to find Marie and her family, and mostly came up with mentions of the Russian spy, Walter Krivitsky (real name Samuel Ginsberg). I started putting together a few family trees for other Krivitzkys who might be related.

But in 2016 I visited Philip Goldenberg, who is my second cousin once removed, and he suggested that I contact Penny Martin (née Samuels), another second cousin once removed. (Penny’s mother Rose Katz was my grandmother Judy’s first cousin.)

Simplified family tree

Penny wrote that:

“I met Marie K., some time in the early 1960s, when I and my best friend were invited to her flat for tea, which was actually an excellent apricot tarte and some beer, which we enjoyed on the huge terrace of her flat in Cannes. … I think, at some stage, Krivitski became Katz.”

So now I knew that the connection was definitely on the Katz side, but it wasn’t easy to find any records in Ekaterinoslav (now Dnipropetrovs’k) in Ukraine, where the family had come from.

In 2020 I found her birth certificate, and started to piece her family together.

Record from Jewish Record Indexing-Poland, image from https://metryki.genealodzy.pl/

Marie had been born in Warsaw in 1910, and her parents were Erachmiel and Zysla Gitla née Ruzewicz. And I found a record on the French genealogy site, https://en.filae.com, showing that Marie had died in 2003 in the south of France.

I guessed that the headed notepaper Marie had used was her father’s, and that he had changed his first name from Erachmiel to Roman when he moved to France.

In March 1921, Marie’s mother died in Paris. This is the death record from the Paris Archives:

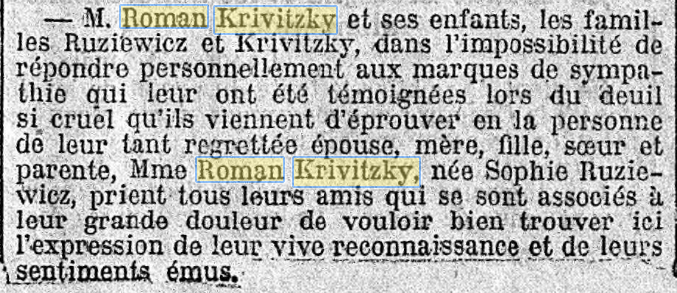

She was buried in Père-Lachaise Cemetery. This announcement was published in Le Temps, on 15 March 1921, p. 5.

Marie’s father, Roman, was transported to Auschwitz from the Drancy internment camp on 28 October 1943. I found a website which says that “Convoy 61 departed on 28 October 1943 from the Paris-Bobigny station at 10:30 a.m. with 1,000 Jews on board. The convoy arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau on 30 October 1943 where 284 men were selected for forced labour and tattooed from numbers 159546 to 159829. The following day, 31 October, 103 women were selected for forced labour and tattooed from numbers 66451 to 66553. The remaining 613 deportees are gassed as soon as they arrive.”

Various documents relating to Roman can be seen on the Mémorial de la Shoah website. A notebook records that, at the time of his arrest, he was in possession of a Longines gold and silver watch, a gold chain and a gold signet ring with a stone. These were all confiscated.

His name is inscribed on the wall of names at the Mémorial de la Shoah in Paris, and on 28 October 2023 a ceremony was held in Paris, at which the names of the deportees were read aloud.

The crypt at the Mémorial de la Shoah. By BrnGrby - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=87428743

(Surely there must have been family letters during the war, trying to find out whether cousins were safe, but I have not found any.)

If my grandmother Judy and Marie were actually second cousins, then her father (my great-grandfather) Maurice Katz and Marie’s father Roman must have been first cousins, and my great-great-grandfather Isaac Katz and Roman’s father must have been brothers. I needed to find Roman’s father!

Back in 2020, I had been in touch with Katya Bregman, who is a third cousin on a different branch of my family, and she showed me how to obtain records from the State Archives of Dnipropetrovsk Region. I asked them to send me any Katz and Krivitzky records they could find.

Reading them with my phone, using Google Translate, one says:

“For the year 1876, there is a record no. 163 about the birth of a male child named Erachmiel on September 7, 1876. Parents Kremenchug burgher Abram Ilya Osipov Kryvychky and Sarah. The rite of circumcision was performed on September 14, 1876.”

This birth date matched the one on the deportation list from 1943, so I was sure this was correct. I found Kremenchuk in Ukraine (I guess we’re all more familiar with these place names now.)

Kremenchuk, central Ukraine. Map data © 2023 Google.

So now I had the names of Erachmiel (Roman)’s parents. With a name to look for, I found a death announcement published in Warsaw, for an Abram Krywicki who died in Paris in 1925.

Nasz Przegląd, 6 May 1925, p. 7.

This says that he died suddenly, and mentions that he left daughters, sons, daughters-in-law, sons-in-law, granddaughters and grandsons. This is his French death record, which says that he died on 2 May at his home, 50 rue Desbordes-Valmore in the 16th arrondissement of Paris. It tells us that he was born in Ekaterinoslav, and was aged 77 when he died. He was the widower of Esther Nieginsky.

Map data © 2023 Google. The address is the door with the P sign in front of it.

It seems reasonable that Abram, born in Ekaterinoslav in 1848, could be the brother of Isaac, born in the same place in 1842. I knew from Isaac’s grave that his father’s Hebrew name was Yehuda Leib (in Russia probably Lev or Leon), and putting this information into a simplified tree, we can now see the relationship.

I had seen a notice in a French newspaper, the Journal Officiel de la République Française, suggesting that Roman had applied for French citizenship, but at the time the Archives were closed because of Covid, and I didn’t pursue it.

Journal Officiel de la République Française, 25 Jan 1926, p. 1083.

After seeing the Paris Archives on a trip to Paris with my mother, Ruth, in June this year, I was reminded of the treasures that lie within, and resolved to try to get a copy of his application.

I asked a French genealogist to help me, and she was able to get the file and translate it. Although this was expensive, it was well worth it. The file contained 124 pages of letters and documents dating from 1923 to 1963, with a huge amount of information that was new to me, especially about his siblings (which I won't go into here).

Front of Roman Krivitzky’s file

In January 1923, Roman wrote to the Minster of Justice, stating that he had been born on 9 Sep. 1876 and his parents were Abraham Krivitzky and Esthère Niéjinsky. He said he had come to Paris in 1919 in order to sell tobacco to the French government, having been sent by General d’Anselme, commander of the 1st Division Group of the Allied Army of the Orient on the Macedonian front.

He mentions his three children: sons Stanislas (19) and Paul (9), and a daughter, Marie (17).

He says that he is the chairman of the Kyriasis Cigarette Company based in Brussels. (This is the Egyptian company, Kyriazi Frères.)

Cigarette tin. By Mazkyri (talk) - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=36730928

I found this notice of their AGM from September 1922 in the Belgisch staatsblad on Google Books:

He is also the owner of the Ruziewicz and Krivitzky oilcloth factory in Warsaw and other businesses in Russia.

Roman goes on to say that he can’t obtain his own or his father’s birth certificates from Russia.

The request was then sent to the Prefect of Police, who was asked to provide further information and documents. He recommended rejection of the application, saying that Roman had been the subject of an anonymous denunciation accusing him of maintaining relations with Bolsheviks, and also that there was an ongoing investigation into embezzlement.

In September 1923 the Prefect of Police says that he has no objection to Roman’s application being considered, and also tells us that Roman had a shoe and leather factory in Moscow, supplying the Russian army.

In 1925, Ernest Vallier, Attorney at the Court of Appeals, asked on Roman’s behalf if the naturalization application could be considered again. Roman’s son, Stanislas, also writes, saying that he is now 22 and wants to fulfil his military service, so would be grateful for a prompt decision.

In May 1925, he was told that he hadn’t been living in France for long enough to meet the criteria, so could only apply for admission to residence. On 14 January 1926, Roman was granted domicile. A week later, he wrote to request naturalization. At this point, the Prefect of Police recommended that, although the information gathered about Roman was favourable, the request should be put off until Stanislas applied (which he did in February 1927). Roman then wrote again, saying that his son was very keen to complete his military service. He was asked to come to the Ministry of Justice at 4 o’clock on the afternoon of 24 February.

In April, Roman was asked to pay duties of 1299 Fr. for the naturalization, after which he would receive his documents. He also apparently owed 214,892.52 Fr. in taxes dating back five years, but said that he had to get money from Russia and proposed staggering the payments. In October, because he lived in a private mansion worth 800,000 Fr. but was avoiding paying taxes, it was recommended that he should be expelled (this would require the settlement decree received in 1926 to be revoked). In January 1928, Roman was told that no action would be taken regarding his application until his taxes had been paid. In March 1928 the proposal to expel Roman was submitted to the Minister of the Interior, and the expulsion order was issued.

In February 1929, Roman wrote to the naturalization department, saying that he was now up to date with his taxes. (The expulsion order was apparently repealed in November 1928, after he had paid the arrears.) The Prefect of Police now regarded Roman’s application favourably, but there was a delay while an updated statement was requested.

In January 1931, Roman wrote to the Minister of Justice again, and the Prefect of Police offered no objections.

In May 1932, the Minister of Justice summarized the case, saying that there was no opposition from the Foreign Office, or the Ministries of Commerce and the Interior. Full naturalization was proposed, and Roman was asked to attend the Ministry of Justice on 18 June. The following week, the Minister of Foreign Affairs was asked to gather information about Roman’s activities abroad. It mentions the oilcloth factory at 84 Czerniakowska Street in Warsaw, which was now being managed by Stanislas. It says that during the war, Roman was living at 26 Twierskaja Jamskaja in Moscow, and that he went to live in Yalta in 1918. The Minister of the Interior saw no reason not to consider Roman’s application (letter dated 4 July 1932). A letter from the French Consul in Warsaw in September 1932 stated that Roman had lived in Warsaw between 1905 and 1915, and confirmed that he was the co-owner of a factory and building in the city. In October the Paris Chamber of Commerce approved of Roman’s naturalization.

On 14 October 1932, Roman was asked to pay 1299 Fr. He would then receive his naturalization documents two months later. In November, the senator Gaston Bazile inquired into progress on the matter.

Journal Officiel de la République Française, 27 Nov 1932, p. 12341.

As we know, Roman had been killed at Auschwitz in 1943, and the next letters in the file are from November 1962, when Marie wrote to the Minister of Public Health and Population. She had been trying to renew her passport in Cannes and had been asked to provide a copy of her naturalization certificate. She said that her brothers Stanislas and Paul were both French citizens and had completed their military service and participated in the Campaign of France in 1939.

She was informed that no record could be found of her French nationality, and that she would not have benefited from Roman’s naturalization by decree in 1932, as she was an adult at that time. She wrote back in November 1963, saying that she had always believed herself to be French. She had a French passport, she was the daughter of a French citizen and a deportee. Her brothers had served in the military, all her family lived in Paris, where she had studied as an artist (at the Lycée Victor Duruy, Ecole du Louvre and the Musée d'Art et d'Archéologie). She was then told that the law under which she was applying for French nationality only applied to women who had married a French national, so she would need to go through the naturalization process herself.

This photo of Marie is undated and was taken in Paris.

This one was taken in the 1950s, in Cannes (l. to r. Wladyslaw Schneid, Judy, Laurie Neale, Harry, Marie).

Comments